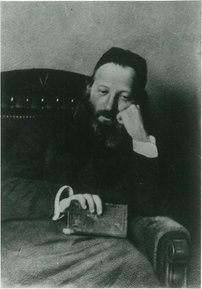

In Honor of the Eightieth Yahrtzeit of Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook: A Brief Overview of His Life8/18/2015  For teachings of Rav Kook, please visit ravkook.net. Rav Kook by Rabbi Netanel Elyashiv Rav Netanel Elyashiv is the rosh yeshiva of the preparatory yeshiva Bnei Dovid in Eli and manager of the publishing company, Binyan HaTorah. Thanks to Rabbi Avraham Wasserman, author (with Eitam Henkin) of Lehakot Shoresh. The following is my translation from the Hebrew original, which appeared in Olam Katan. Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaCohen Kook was born in Elul 5625 (1865), in the town of Griva, Latvia. He had an unusual background: his father was a Lithuanian Torah scholar (a misnaged), and his mother was from a Hasidic (Chabad) family. At the age of eight, his father, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman, took him out of cheder in order to teach him himself. When Rav Kook was seventeen, Rabbi Israel Salanter, the father of the musar (ethics) movement, passed away. The young Rav Kook felt such a deep sense of identification with him that he tore his clothes in mourning. When Rav Kook was eighteen, he was engaged to Alta Bat-Sheva, the daughter of one of the outstanding Torah sages of the generation, Rabbi Eliyahu Dovid Rabinowitz-Te’omim (the Aderet). Until they married, he learned for over a year in the “mother of yeshivas,” the Volozhin yeshiva. Although he did not learn there for a very long period, this was a meaningful and defining time for him. For a number of years, when the young Rav Kook would meet his rabbi, the Netziv (rosh yeshiva of the Volozhin yeshiva), the latter would have a meal involving meat even during the Nine Days of mourning preceding Tisha B’Av, because this was a meal in honor of the Torah. At the age of twenty, Rav Kook married Alta Bat-Sheva and they had a daughter (Frayda Chanah). Tragically his wife passed away after they had been married for only three years. He then married her cousin, Reiza Rivka, who mothered all of his other children: Rabbi Tzvi Yehudah, Basya Miriam (who married Rav Raanan) and Esther Yael, who passed away in her youth. In truth, he had no desire to be a professional rabbi, but Rav Yisrael Meir Kagan (the Chafetz Chaim) pressed him to agree to any request he received that he serve as rabbi, and the Chafetz Chaim immediately saw to it that the community of Zaumel, Lithuania, would offer him a post. And thus Rav Kook was appointed to his first position. After six and a half years there, Rav Kook moved to a large community in the town of Bausk, in the south of Latvia. During this time he wrote down his sermons in a book called Midbar Shur. These sermons indicate that even then Rav Kook was brilliant and innovative. He cited clear sources for his statements, but in the course of time he reduced the citation of sources in his non-halachic writings, thus leaving a great deal of work for his interpreters and ammunition for his critics. Also, during his years in Bausk he wrote the majority of his commentary on the aggadah in the Talmud, Ein Ayah. In 5668 (1908) he wrote to someone that the printing of Ein Ayah was being delayed due to a lack of funds. Printing continued to be delayed, and the first volume in the series was printed only ninety years later, in 5755 (1995). A look at his earlier writings shows clearly that he had a vast command of all parts of the Torah: Talmud, halachah, Tanach, midrash, Jewish thought, and a special connection to kabbalah, with an emphasis on the writings of the Ari and the Ramchal. It is clear that he was expert in the world of philosophy and secular studies, although he did not explicitly cite non-Torah sources. The Journey Sets Out Rabbi Yoel Moshe Salomon, who founded Petach Tikva, also initiated Rav Kook’s immigration to the land of Israel to be rabbi of Jaffa and the surrounding areas. On 28 Iyar 5664 (1904), these efforts bore fruit, and the Kook family came to Jaffa. Rav Kook was then 38 years old. Only one week later, on Shavuot, a young Torah genius from Jerusalem, Yaakov Moshe Charlop, came to Jaffa to spend the holiday with Rav Kook. From that day until Rav Kook passed away, Rav Charlop clung to him with all his might. During this period, Rav Kook met directly with the young generation of the pioneers of the first and second waves of aliyah. Very quickly he reached the conclusion that it was impossible to relate to the heretical spirit held by some of them in the same way that Jews had related to the heretics of previous generations. He recognized that this was a different phenomenon. He wrote his thoughts on this topic in his “The Generation,” a historically significant essay that is learned in many Torah institutions to this day. Already then extremists saw him as a “dangerous” rabbi, although opposition to him had not yet gained momentum. Towards 5670 (1910), which was a sabbatical year, Rav Kook expressed support for the heter mechirah, which allows maintenance of Jewish agriculture in the land of Israel even in a sabbatical year, subject to certain halachic restrictions. Rav Kook did not introduce this heter, which was solidly based on rabbinical guidance for previous sabbatical years, but the dispute in his time between the old and new communities turned particularly explosive. To this day, the dispute around the heter extends beyond its true halachic dimensions. Overall, Rav Kook tended to be strict in halachah. In regard to the heter mechirah, he was stricter than the rabbis who had preceded him and he forbade “Torah level” work performed by a Jew (for which he was criticized by the workers). Rav Kook encouraged Meir Dizengoff (who eventually founded Tel Aviv), “You will build a city.” Dizengoff was close to him and strove to accept his directives. In 5683, Rav Kook succeeded in passing a city ordinance in Tel Aviv to keep the Sabbath in the public sphere. At the beginning of the winter of 5674 (end of 1913,), Rav Kook initiated the “trip to the communities”—a delegation of rabbis to the new communities that the pioneers had established, in particular in the north. This journey lasted almost a month, and in its course the rabbis visited about 26 communities. The purposes of the journey were to encourage the settlers religiously and to bring the old and new communities closer to each other. Rav Kook’s ideological opponent, Rabbi Chaim Sonnenfeld, participated in the journey. Additional journeys took place in 5684 (1923) and 5687 (1927). Despite his expressions of love for secular Jews, Rav Kook did not withhold piercing criticism of them when he found that appropriate, at times speaking quite sharply. Forgiving Slanderers After difficult and extended considerations, in the summer of 5674 (1914) Rav Kook left the land of Israel in order to participate in a major conference of the new Orthodox (chareidi) movement, Agudath Israel. Rav Kook envisioned a massive aliyah of chareidi Jews as the key to improving the spiritual situation in the land of Israel, and hoped that it would be possible to advance this goal by bringing Agudath Israel closer to Zionism. The trip, which was intended to last a few weeks, ultimately lasted five years, because a short while after Rav Kook came to Germany the First World War broke out and it was impossible to return to the land of Israel. The terrible world war, the scope of whose bloodshed was without precedent, shocked Rav Kook deeply, and in those years he dealt at length with the meaning of the war from a spiritual perspective, and with the hope that it would lead to significant progress in the process of the redemption. And in fact, in the course of the war the land of Israel passed from the Turks to the British, and the English government published the Balfour Declaration. Rav Kook’s daughters remained alone in the land of Israel during those difficult years, while his son, Rav Tzvi Yehudah, joined him, and in the course of more than a year they lived together, relatively at leisure, in Switzerland. Later, Rav Tzvi Yehudah said that at this time together with his father he went “through the entire Torah a number of times.” Throughout all of these years, beginning with his days as a rabbi in Bausk, Rav Kook wrote a wealth of spiritual thoughts in booklets and notebooks in which he unfolded the inner world of radical holiness with free and original thought. These notebooks formed the basis of his books in a variety of subjects, such as Orot Hatorah, Orot Hateshuvah, Orot Hakodesh, Orot and Olat Rayah. At the time that Rav Kook was in Switzerland, Rabbi Dovid Cohen (the “Nazir”) became his especially close student. At first, Rabbi Cohen came only to speak with Rav Kook about Torah and wisdom, but after one particularly moving morning prayer in the company of Rav Kook he wrote: “I have found more than I had hoped for: I have found myself a mentor.” During the course of the war Rav Kook served as rabbi of the central community in London. Thus, it came about that he was in England at the time of the formulation of the Balfour Declaration, where he engaged in a public debate with those Jews who opposed it. In 5678 (1918), Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank began to campaign for the appointment of Rav Kook as rabbi of Jerusalem. A clear majority of the rabbis of the city supported the process out of appreciation for his greatness in Torah, as well as out of hope that, with his stature and world-renown, he could help restore the world of Torah that had been badly harmed during the war years. However, zealots opposed this strongly. In the beginning of 5680 (1920), Rav Kook became chief rabbi of Jerusalem. In the course of that year he published the book that many see as his central work, Orot. But that opened wide the gates of controversy, for the zealots saw in it support for their negative view of Rav Kook. They interpreted his words in praise of the national revival and those working on its behalf as sycophancy of wicked people and as a grave perversion from the principles of Judaism. Coarse wall posters were published in the streets of the city and booklets slandering Rav Kook were sent overseas. Rav Kook accepted this reaction with noble forgiveness, and at times even defended his opponents. He also knew that most of chareidi Judaism was with him. One of the bases of central support for him was the neighborhood of Meah Shearim—ironically, since today Meah Shearim is the opposite in its nature. Nevertheless, the dispute, which was accompanied by ugly incitement and coarse insults, took its toll, so much so that later on his son blamed the zealots with causing the onset of the illness that led to his father’s death. As a result of a passage in Orot in praise of physical exercise, the zealots accused Rav Kook of supporting Maccabi soccer games on the Sabbath, although in truth he protested ceaselessly against this phenomenon and even sent colleagues from Bnei Akiva to protest a Sabbath game. A National Leader At this time Rav Kook attempted to set up a broad popular movement called Degel Yerushalayim in order to supply the spirituality lacking in Zionism. This step came out of his sense that the Mizrachi moment (from which religious Zionism sprang) was too compromising, and could not compete for leadership of the Zionist movement. In general, it is well-known that Rav Kook supported Zionism—but few know that at the same time he was among its most fierce critics. All of his days he worked with all his might in order to connect Zionism to its holy source. Despite individual successes, the movement was not elevated. It appears that his idea was premature. In his years in Jerusalem, Rav Kook realized two great dreams: he founded the chief rabbinate in the land of Israel and established the Central World Yeshiva (Merkaz Harav), in which students learn Tanach and Jewish thought, something that was innovative in the Torah world. In this, he realized part a certain part of the vision of the Degel Yerushalayim movement. During these years, he also became a national leader of the first rank, as he established connections with leaders of the future state of Israel, with chief figures of the British mandate, with great Torah personalities who visited the Holy Land such as the Hasidic rebbes of Gur and Lubavitch, and with important people such as Albert Einstein. He was a participant in the battle to establish the state of Israel. He defended the honor of the Jewish community at the time of the events of 5689 (including the Arab pogrom in Hebron) and represented the community in various committees, such as the committee that investigated the events of 5689 and another committee that was set up to determine ownership of the Western Wall. He stood strong as a rock against intense pressure that brought to bear on him, refusing to sign a declaration that the Wall belonged to the Arabs and that Jews only had the right to pray there. Aided by his son Rav Tzvi Yehudah, Rav Kook worked hard to bring Jews to the Holy Land—in particular, persecuted Torah scholars from Russia. Rav Kook was profoundly appreciated by the Torah sages of the generation, including those who opposed parts of his teachings. The Chazon Ish, for example, referred to him as maran, “the master,” and when Rav Kook came to Bnei Brak for a ceremony laying the foundation stone of the Novardok yeshiva, the Chazon Ish stood for the course of his entire speech, saying, “The Torah is standing!” Later, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, halachic decisor of the generation, said of him that “there were no great leaders like him in his generation. His greatness was unique. The rabbi was great not only in his own generation but for generations.” And he said, “When I refer to ‘the rabbi,’ I mean Rav Kook—that is my rabbi.” When Rav Kook was 68 years old, in 5694 (1934), he was attacked vigorously by the (leftist) secular community for his participation in defending accused of the murder of Haim Arlozorof, one of the leaders of the Poalim movement. Rav Kook was convinced that they were falsely accused, and in the end they were indeed vindicated. Rav Natan Milikovski, the grandfather of Binyamin Netanyahu, was the one who convinced Rav Kook to involve himself in this matter. The Dreams That Were Realized and Those That Have Not Yet Been Realized On Adar 1 5695 (1935), Rav Kook traveled to Tel Aviv to speak at a gathering in support of Sabbath observance. On the way back to Jerusalem, Rav Kook felt pains in his abdomen. In the month of Nissan his pains grew worse. He grew weak and appeared feeble, he contracted a fever and his appetite faded. Shortly afterwards he was diagnosed with cancer. He endured difficult months, during which he continued to write, to receive people as well as he could and to learn Torah. At a certain stage, his physician recommended that he be transferred to a hospital in Kiryat Moshe. Although he hoped for good, he knew that the chances were great that he would never return to his home and study hall. Before he left, he went through all of the rooms of the house and study hall, and he asked that the car bringing him to the hospital drive through all of the parts of the city that was so beloved to him. On 1 Elul the Nazir came to his sickbed with the first pages of Volume One of Orot HaKodesh, which he edited from Rav Kook’s notebooks. Rav Kook looked at the title page of the book, and laughed and cried. Psalms were recited across the Jewish world. On 3 Elul a group of rabbis and friends were brought into his room. Rav Kook turned his face to the wall, as the physician cleaned his body of the blood that streamed from it. When the signs of his imminent death appeared, the visitors declared loudly, “Hear O Israel, Hashem our God, Hashem is one.” Rav Kook turned to them and recited the verse with them, and as he pronounced the word “one” his soul left his body. Heavy mourning fell upon the Jewish world, and in particular upon the Jews of the land of Israel, who rightly felt that they were orphaned. Since that time, eighty years have passed. Many of Rav Kook’s dreams have been realized: a state of Israel has arisen, millions of Jews have come to the land of Israel, a large teshuvah (repentance) movement is flowering, tens of thousands of Jews learn his writings and attempt to realize them, according to their understanding and their abilities. On the other hand, the way is still long. But Rav Kook said, “Even if the way appears to be long, let us not be overwhelmed.” Thank God, there are many commentators on his words who open the gates of understanding to his deep ideas. Nevertheless, there is no substitute for drawing from the original well. “Taste and see that Hashem is good.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Yaacov David Shulman

Archives

October 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed